Day 20

Mycenae is a little place that has been occupied by mankind for at least 7,000 years.

As usual with archeologists, the story seems to be coming in waves: neolithic, pre-hellenic, bronze ages, Helladic... But let's not be fooled: people kept making babies, they kept producing or gathering food and eating with their mouths, they kept being industrious and curious and daring, and they had to adapt or to go extinct when stronger forces forced them to do so, and all of that happened in a continuum.

The site was built as a stronghold, on top of a small hill. It is neither as high or as wide as a small castle, but one cannot dismiss the size of the stones used for the foundations and outer walls – much larger than those of castles – nor forget that these foundations were laid a few thousand years before your preferred castle was built. Impressive and rather elegant.

The site feels compact rather than small, and practical rather than show-off. The palace at the top was small, and yet it seems the city developed trading relationships way beyond its neighbouring shores. The city itself was built-over and extended several times, e.g. in order to facilitate craft people's activities and to create underground water reserves.

This area developed very specific art and aesthetics.

Through the visits to the site and the museum it seemed to me the city hosted a tight knit community close to the so-called teal organisations, despite the clear indications of inequalities of all sorts.

It provides a strong contrast to the travellers who are witness to the abandoned villages, to the disused or unfinished and non-inhabitable concrete buildings that are visible in every town, along many roads and many beaches. It is not only in Greece. This exists in most of the countries of the old continent where I've been so far. We live in a society that defines itself by waste.

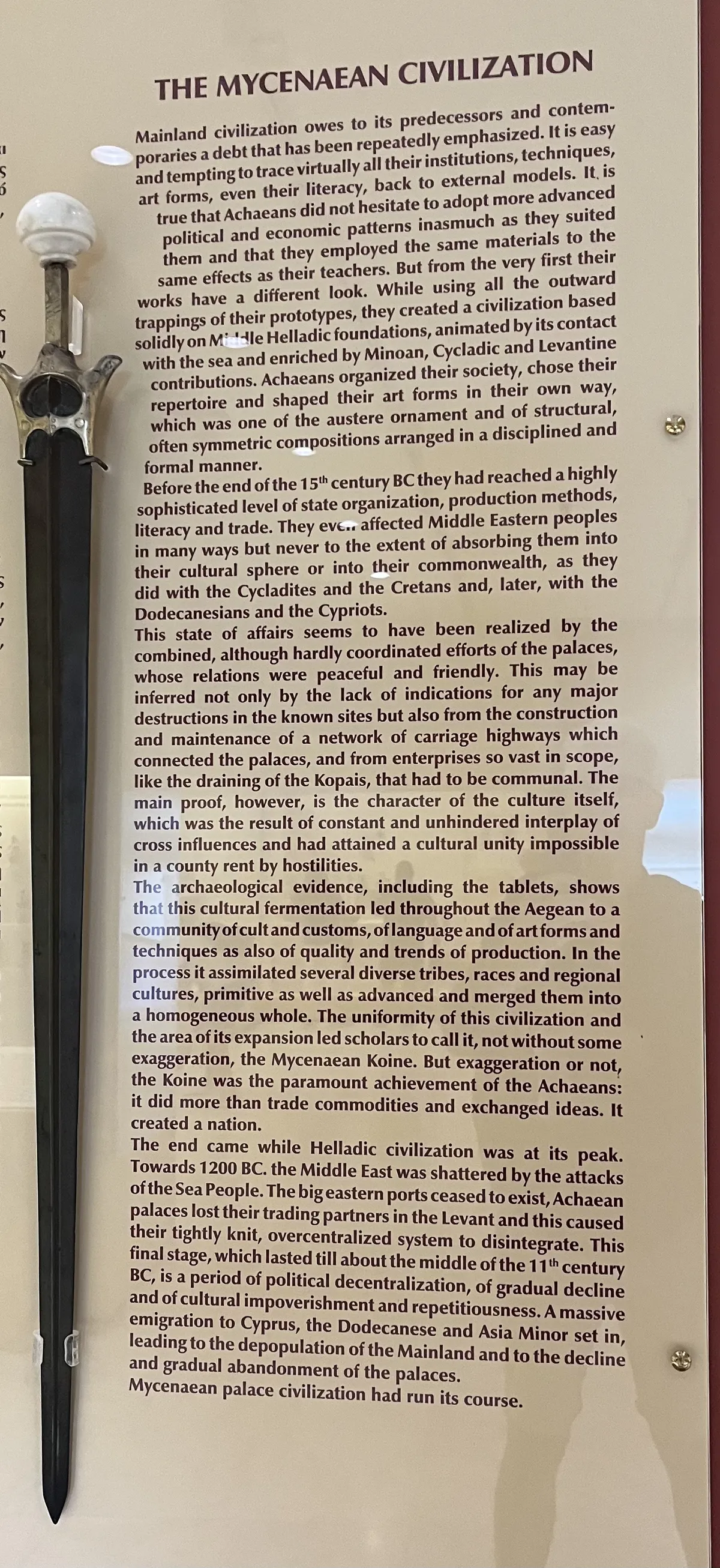

Here is a piece to ponder upon, transcribed below as to allow for translation.

THE MYCENAEAN CIVILIZATION

Mainland civilization owes to its predecessors and contemporaries a debt that has been repeatedly emphasized. It is easy and tempting to trace virtually all their institutions, techniques, art forms, even their literacy, back to external models. It, is true that Achaeans did not hesitate to adopt more advanced political and economic patterns inasmuch as they suited them and that they employed the same materials to the same effects as their teachers. But from the very first their works have a different look. While using all the outward trappings of their prototypes, they created a civilization based solidly on Middle Helladic foundations, animated by its contact with the sea and enriched by Minoan, Cycladic and Levantine contributions. Achaeans organized their society, chose their repertoire and shaped their art forms in their own way, which was one of the austere ornament and of structural, often symmetric compositions arranged in a disciplined and formal manner.

Before the end of the 15h century BC they had reached a highly sophisticated level of state organization, production methods, literacy and trade. They ever affected Middle Eastern peoples in many ways but never to the extent of absorbing them into their cultural sphere or into their commonwealth, as they did with the Cycladites and the Cretans and, later, with the Dodecanesians and the Cypriots.

This state of affairs seems to have been realized by the combined, although hardly coordinated efforts of the palaces, whose relations were peaceful and friendly. This may be inferred not only by the lack of indications for any major destructions in the known sites but also from the construction and maintenance of a network of carriage highways which connected the palaces, and from enterprises so vast in scope, like the draining of the Kopais, that had to be communal. The main proof, however, is the character of the culture itself, which was the result of constant and unhindered interplay of cross influences and had attained a cultural unity impossible in a county rent by hostilities.

The archaeological evidence, including the tablets, shows that this cultural fermentation led throughout the Aegean to a community of cult and customs, of language and of art forms and techniques as also of quality and trends of production. In the process it assimilated several diverse tribes, races and regional cultures, primitive as well as advanced and merged them into a homogeneous whole. The uniformity of this civilization and the area of its expansion led scholars to call it, not without some exaggeration, the Mycenaean Koine. But exaggeration or not, the Koine was the paramount achievement of the Achaeans: it did more than trade commodities and exchanged ideas. It created a nation.

The end came while Helladic civilization was at its peak. Towards 1200 BC. the Middle East was shattered by the attacks of the Sea People. The big eastern ports ceased to exist, Achaean palaces lost their trading partners in the Levant and this caused their tightly knit, overcentralized system to disintegrate. This final stage, which lasted till about the middle of the 11th century BC, is a period of political decentralization, of gradual decline and of cultural impoverishment and repetitiousness. A massive emigration to Cyprus, the Dodecanese and Asia Minor set in, leading to the depopulation of the Mainland and to the decline and gradual abandonment of the palaces. Mycenaean palace civilization had run its course.

Later on we went back to the coast, to eat and find a place to sleep.